The Big Burn

Chapter 7 from The Story of Yellowstone

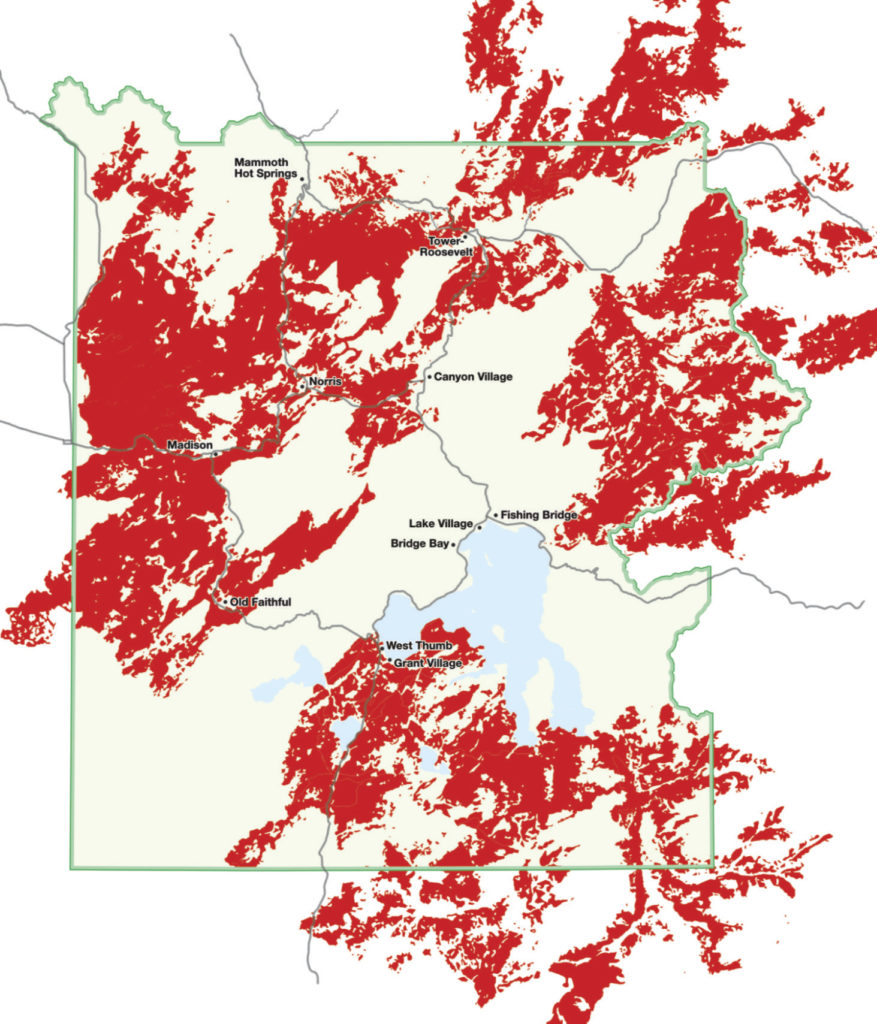

Waves of red and orange flames rose hundreds of feet above Yellowstone’s forests as columns of thick black smoke billowed five miles into the sky, blocking out the sunlight. Strong winds stoked the fires, launching embers a mile or more ahead of the flames, and spreading them as much as 10 miles a day. Virtually no rain fell for three months that summer in 1988, and the fires failed to subside at night as the humidity remained unusually low. By the time rain and snow dampened the flames in September, 10 fires had blackened more than 2,100 square miles of Yellowstone Country, more than half of which lay in the park.

Lightning ignites fires nearly every year in Yellowstone. The flames usually die out after burning a single tree or small area, thus park managers weren’t alarmed when several such fires ignited in June. But when the right conditions exist, wildfires spread quickly as eventually happened during that parched summer.

Extensive burns in Yellowstone are closely associated with lodgepole pine, the dominant tree in the park’s forests, where four of every five trees are lodgepoles. That ratio is even higher on the Yellowstone Plateau, where little else grows in the quick-draining and poor rhyolitic soil. The shallow, horizontally spreading roots of lodgepoles enable them to absorb rain and snowmelt before the water seeps deeper underground and out of reach.

Sun-loving lodgepoles depend on fire to clear the forest floor and to spread their seeds. Indeed, these trees share an extensive history with fire in Yellowstone, going back 11,000 years, about 1,000 years after glaciers had receded from the area. Inside the resin-sealed cones of mature lodgepoles, the seeds of new forests slumber, awaiting the heat of fire to free them. When that heat arrived in 1988, it melted the waxy resin and scattered millions of seeds. The flames also reduced to ash decades-old and even centuries-old accumulations of dead needles, branches and logs on the forest floor—recycling nutrients much quicker and more thoroughly than bacteria, fungi and other decomposers can do in the generally cool, dry Yellowstone climate. And the fires released even more nutrients as they burned live limbs and forest understories.

Forest fires rarely consume all the trees within their perimeters—even fires as intense as in 1988. Damage varies in degree, from fully torched trees to intact ones, creating a mosaic of black, rust, gray and green. Over time, a mix of habitats with greater diversity takes shape, rooted in the varying species and ages of trees and plants. A 25-year-old lodgepole forest hosts more than twice the number of bird, mammal and plant species than one at least twice that age. Living trees, as well as fallen ones and standing deadwood, provide shelter and food for a wide variety of insects, birds and other animals.

In the spring and summer following the fires, moisture from snowmelt and rainfall helped mineral-rich ash seep into the soil. Sunlight warmed the earth, and lodgepole seeds sprouted thickly. In the ensuing years, dense stands of young lodgepoles competed for sunlight, water and nutrients. As larger trees shaded smaller ones and overhanging branches blocked the sun from lower ones, the weak branches died and eventually fell. Over time, more and more trees and branches lost out and died.

The seeds and roots of burned and once-shaded plants also sent up lush new growth during the spring and summer of 1989. Sun-loving Bicknell’s geraniums sprouted, their seeds having slumbered for two centuries or more. These pale pinkish-lavender wildflowers grew for two years, dispersed their seeds and then died back, awaiting another fire to be reborn. Also, the pink of fireweed, the yellow of heartleaf arnica and the blueish purple of lupine radiated against the backdrops of blackened trunks in newly opened, sun-drenched areas. Grizzly bears fattened up on the fireweed, clover and other plants in burned areas during the several lush years following the fires.

Dense shoots also emerged from quaking aspen roots after the fires. Some of the aspen groves have root systems dating back more than 10,000 years, making them the oldest living organisms in the area. Aspens typically grow more quickly by cloning themselves from shoots than by sprouting from their tiny, wind-blown seeds. Those seeds must take root in bare patches of soil and then receive consistent moisture with little competition during the next few years. Following the ’88 fires, aspens actually did manage to spread to new areas from wind-dispersed seeds, including onto the plateau.

For more than 100 years, aspens have declined in the northern areas of Yellowstone, their stronghold, where they grow at the edges of forests and along floodplains and stream banks. With a drying climate and, until recently, high densities of elk browsing heavily on shoots and young trees, aspens died back to about a third of their former range.

More recently, since the restoration of wolves in Yellowstone, elk numbers have dropped to levels more suitable for the land that supports them, and aspen appear to have benefited from less browsing pressure. As they did with wolves, people also suppressed fire for much of the last century, which allowed conifers to outcompete aspen and close up forests. Today, naturally occurring fires are usually allowed to burn, yet the benefits of fire for aspen could be offset by the rapidly changing climate.

In cooler, wetter areas downslope from the poor soils of the Yellowstone Plateau, shade-tolerant Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir dominate older forests. They grow in the richer soils formed from the andesitic lava of the Absaroka Volcanic Supergroup era. The thin-barked spruce and fir burn easily, but in the absence of fire, they often take root below mature lodgepoles, shade out their seedlings and eventually take over.

Douglas fir also grows in the andesitic soils found off the plateau and has adapted to fire through the eons by growing thick bark that protects it from less intense burns, which occur every 25 to 60 years in the Lamar Valley and other places in the park. The newest of the tree species in Yellowstone Country, Douglas fir seeds blew in about 7,000 years ago. Away from forests, Douglas fir seeds often sprout next to boulders dropped by glaciers, including the thousands scattered about from Tower Junction through the Lamar Valley. The shadows of these nurse rocks retain moisture for the fledgling trees in an otherwise arid landscape.

Whitebark pine grows in steep, rocky ground from an altitude of 7,000 feet up to timberline, where it outcompetes other trees and tolerates fire better than spruce and fir. Whitebarks take many decades to reach maturity and produce pinecones, and cone production varies by area and from year to year. When these cones are available, grizzlies, red squirrels and Clark’s nutcrackers feed heartily on the fatty nuts inside. It takes the crushing power of bear jaws, the persistent chewing of squirrel teeth and the stout beaks of jays to crack into the hard cones to reach the nuts.

Some black bears also climb whitebarks for the cones, but grizzlies, who rarely climb trees, let squirrels do the gathering and then raid their caches. Chattering squirrels vigorously defend their stashes of cones, but if they protest too much and too closely, a grizzly will devour them, too. Bears need to eat as much as possible in late summer and autumn before hibernating. They can gain nearly three pounds a day during that period, especially when high-caloric pine nuts are available.

Clark’s nutcrackers, like squirrels, also stash seeds for winter and for the next nesting season. At the tops of whitebark trees, nutcrackers strike their chisel-like lower jaw into the seams of the cones to extract the nuts. They stuff as many as 150 pine nuts into their throat pouches and fly off to bury them in caches, sometimes miles apart. Using landmarks, such as logs, rocks and trees, the nutcrackers return to most of their hundreds of caches during the winter and spring to feed themselves and their young. Many of their caches lie in snow-free, windswept areas, but the birds sometimes must sweep away deep snow to reach their stores.

Unlike other jay and crow species, both female and male nutcrackers sit on their eggs, allowing the other to fly off to retrieve the nuts they stored the previous year.

In lean whitebark cone years, nutcrackers in the Yellowstone area seek seeds of the less common limber pines, which are closely related to whitebarks, and they eat just about anything else they can find. Nutcrackers will sometimes fly long distances searching for cones.

New growth of whitebark pine trees depends almost exclusively on nutcrackers forgetting some of their hiding places. Clusters of trees and multi-trunked ones high in Yellowstone Country mark these long-forgotten caches.

The ’88 fires burned more than a quarter of the whitebarks in Yellowstone, and since then mountain pine beetles and white pine blister rust, a fungal disease, have sickened and killed an even greater number than the fires affected. Earth’s warming climate accelerates these infections, and in the decades to come the trees could vanish from Yellowstone Country and other areas, such as Glacier National Park, where some whitebarks are more than 1,200 years old. Clark’s nutcrackers also could disappear since they depend on these trees.

In about an eighth of Yellowstone National Park, far below whitebark country, meadows, sagebrush and grasslands grow in the clay soils left behind by melting glaciers. Had ice not covered the park, the Lamar and Hayden Valleys and other open areas would be thickly forested and home to far fewer elk, bison and pronghorn antelope. About every two decades, fire also burns through these areas and kills small trees that might otherwise establish forests and shrink the grasslands. Although sagebrush, grasses and other plants die back during fires, their roots feed on nutrients from the ash and send up lush new growth afterward.

Just as trees and other plants have adapted to fire, so has wildlife. As the ’88 fires raged behind them, elk grazed in smoky meadows and grizzly bears dug for roots in blackened soil. They skirted the approaching flames but remained near good forage, just as they’ve done for thousands of years. And at least one curious black bear poked at a burning log with its paw, perhaps licking up ants escaping the flames.

Few large animals died in the ’88 fires, but the ones that did usually succumbed to choking smoke rather than flames. The carcasses of the elk, bison, moose and deer that died, like ash from the burned forests, yielded nutrients for grizzly bears, coyotes, eagles, ravens and others. Carnivores also devoured the squirrels, chipmunks, mice, voles and other small animals fleeing the flames. And burned areas provided less cover for prey and easier hunting for coyotes, foxes, weasels, hawks and more.

Of all the animals, moose experienced the greatest long-term effects from the ’88 fires. While just a few of them died that summer, much of their winter forage of willow and old-growth subalpine fir burned. This led to as much as 75 percent fewer moose living in the park today.

Moose migrated into the Yellowstone area relatively recently, however, compared to other species. They moved into the south of the park by the 1880s and into the north a few decades later. They also seemed to have benefited from the lack of fire until 1988.

The severe drought that summer and the severe winter that followed took their toll on other hoofed animals besides moose, at least in the short term. With meager grazing and browsing opportunities that summer and fall, and with deep snow and frigid temperatures that winter, many ungulates starved to death. Nearly a quarter of the park’s mule deer and pronghorn antelope died, about 40 percent of northern Yellowstone’s nearly 19,000 elk perished, and close to 20 percent of the park’s bison died. In many cases, hunters shot the hungry elk when they left the park looking for forage, and wildlife managers and hunters shot many of the bison, as well.

However, tough winters for hoofed animals lead to fat springs for hungry grizzlies emerging from their dens, as well as for coyotes, foxes, ravens, eagles and other scavengers. Also, the 1988–89 winter followed two mild ones with relatively few deaths, and the herds of most animals increased in the years afterward, although moose numbers did not.

Like moose, boreal owls lost much of the old-growth forests on which they rely after the fires. Similarly, some osprey young, still in their nests, burned in the flames, but many bird species benefited from the fires. Cavity-nesting birds found plenty of homes to choose from in burned trees. These include Barrow’s goldeneyes, kestrels, flickers, tree swallows and mountain bluebirds. Dead trees also teemed with insects and larvae for hungry flycatchers and woodpeckers. And open ground below blackened trunks provided more opportunities for ground-nesting birds and for flickers, robins and other thrushes hunting insects and worms.

Seed-eating birds, including Clark’s nutcrackers, finches, crossbills and pine siskins, gobbled up many of the lodgepole seeds dispersed by the fires, but not enough to prevent the growth of new forests. These forests have regreened the blackened landscape, while countless weathered trunks of burned trees stand as a reminder of that year’s widespread fires.

A wind-driven fire burns sagebrush on Yellowstone’s Blacktail Plateau in 1988, two nights before snow and rain dampened the flames for good that year. Jim Peaco, NPS

A view of lodgepole pines from the forest floor. Lodgepoles generally grow straight in Yellowstone, and their lower sun-starved branches drop off over time. Native Americans used younger trunks as tepee (“lodge”) poles. Jacob W. Frank, NPS

Fire mosaic from the 2003 Bacon Rind Fire, which burned in the northwestern area of Yellowstone and adjoining public lands. Author photograph

Young lodgepoles growing amid weathered tree trunks that burned in 1988. Jim Peaco, NPS

Map showing the fires that burned more than a third of Yellowstone in 1988. Adapted from NPS

A mixed aspen-conifer forest in Custer Gallatin National Forest north of Yellowstone. Aspen declined in Yellowstone in the twentieth century because of heavy browsing by elk and fire suppression by park managers, which allowed conifers to outcompete sun-loving aspens. Diane Renkin, NPS

Two bison graze in a smoky meadow in 1988 as a ground fire burns nearby. Jeff Henry, NPS

Grizzly bears are omnivores and benefitted from various food sources after the ’88 fires and the following severe winter. Foods included the carcasses of elk, bison and deer and the lush growth of fireweed, clover and other plants. Jim Peaco, NPS

Yellowstone’s moose population declined significantly after 1988 when that year’s fires burned large swaths of mature subalpine fir, their preferred winter forage. Jim Peaco, NPS

Clark’s nutcrackers are closely linked to whitebark pines, which have dramatically declined in recent decades in Yellowstone because of fire, disease and beetle infestations. Jim Peaco, NPS

Mountain bluebirds are some of the many birds that benefit from fires, which create new and varied habitat. Neal Herbert, NPS